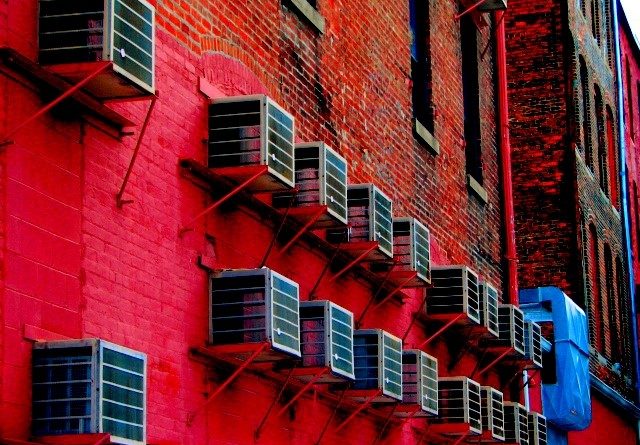

Better air conditioners can help mitigate climate change

Article by Monishaa Suresh

With temperatures around the world rising, we become more reliant on the cool refuge provided by air conditioning. As the global usage and accessibility to air conditioning increases, they have a higher negative and warming impact on our environment, creating an endless and dangerous cycle. However, new research from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California shows that more efficient refrigerating and cooling systems may be part of the solution.

While fixing air-conditioning may not have the same glamorous appeal that electric vehicles and solar panel have, more efficient cooling systems could cut out a degree Celsius of warming by 2100.[1] Although one degree over such a long time period seems insignificant at first glance, the world is projected to increase four to five degrees Celsius if we change nothing and continue “business as usual” and cancelling one of those four to five degrees or 20-25% of the warming, is rather significant.

Currently, most cooling systems are very reliant on hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). These HFCs account for about 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions but are far more potent and dangerous than carbon dioxide emissions. HFCs are considered a sort of “supergreenhouse gas” as they have 1000 times the heat-trapping abilities of carbon dioxide, meaning that while it is less present than carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, its effects are on the same intensity level. Furthermore, while they remain a small percent of overall emissions, if left unchecked, with increased global AC usage, HFC emissions will account for 19% of all greenhouse gases by 2050.[2]

When refrigerants such as hydrofluorocarbons were first introduced, they were lauded for their efficient, non-flammable, and low toxicity characteristics. However, what wasn’t realized at the time was that HFCs have a long atmospheric life, affecting the ozone layer for almost 100 years after first emitted. Today, HFCs are the fastest growing greenhouse gases and usage is increasing 10-15% a year.[3]

The Kigali amendment to the 1987 Montreal Protocol binds nations to eventually phase out HFCs. While industry leaders and scientists have embraced and praised the amendment, its future in the United States is still undecided, as it has been included as a footnote in recent global documents regarding climate change. By increasing the efficiency of air conditioners and curbing 87% of the climate change pollutants found in air conditioners by 2050, we would potentially eliminate 89.7 gigatons of emissions. An act as simple as improving such a ubiquitous appliance would be more effective than building wind farms, decreasing global meat consumption, or a mass crossover to public transport. Increasing air conditioner efficiency alone doesn’t require fancy global treaties – just new regulatory policies as global demand increases.

Sources Cited

[1] Friedman, Lisa “If You Fix This, You Fix a Big Piece of the Climate Puzzle” New York Times (July 13, 2017) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/07/13/climate/climate-change-make-a-difference-quiz.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=photo-spot-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news

[2] Friedman, Lisa “If You Fix This, You Fix a Big Piece of the Climate Puzzle” New York Times (July 13, 2017) https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/07/13/climate/climate-change-make-a-difference-quiz.html?hp&action=click&pgtype=Homepage&clickSource=story-heading&module=photo-spot-region®ion=top-news&WT.nav=top-news

[3] Shah, Nihar, et. al. “Opportunities for Simultaneous Efficiency Improvement and Refrigerant Transition in Air Conditioning” Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (July 2017) http://escholarship.org/uc/item/2r19r76z